*** This piece by guest writer Marietjie Botes was originally published in the February 2014 issue of ‘Without Prejudice’ , a South African Corporate Law journal***

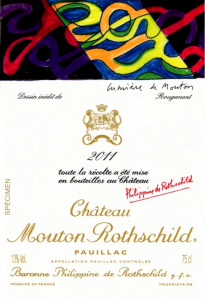

The colourful serpentine lines of the French painter and sculptor, Guy de Rougemont, has become the latest commissioned artwork to adorn the label of Chȃteau Mouton Rothschild’s 2011 Pauillac first growth.

Philippe de Rothschild has been ambitiously marketing his wines by enlisting important artists to create original designs for his wine labels, to enhance the marketing ability of his wines, since the 1920’s. Some of the well known artists include Andy Warhol, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Georges Braque, Francis Bacon, Juan Miró and Lucien Freud. This was of such importance and value to him that he brought out a completely blank label in 1993 in protest against the USA’s refusal to distribute his wines sporting the artwork by French painter, Balthus Klossowski, consisting of a line drawing of a nude woman. And as confirmation of the advertising power of this “mobile billboard” better known as the wine label, this curious situation caught the attention of wine consumers and collectors globally, resulting in enormous profits for Mouton Rothschild. (However, a rock solid history of exceptional wines obviously also helps.)

But, notwithstanding the marketing value of any wine label, it also primarily distinguishes a winemaker’s products from the products of other producers and competitors. Because the character and quality of a wine are not only determined by its varietal, but also directly by the climate, soil and location (terroir) it grows in and viticulture practices of the farmer, it is of utter importance that the origin of the grapes is indicated on the wine label to enable the consumer to make a befitting choice or to ensure that the consumer locates the correct or desired wine. In South Africa such an origin control system has been in place for years. Only if 100% of the grapes, from which the wine was made, come from the same demarcated area, may the label use the abbreviation W.O. or Wine of Origin, followed by the name of the specific production area such as Stellenbosch or Robertson.

Wine labels also serve as visual communicators, educating consumers regarding the wine’s history and heritage such as the quirky Boer & Brit labels designed by the Fanakalo team, Jan Solms and Rohan Etsebeth.

In a 2011 study, conducted by Wine Intelligence, they found that a wine label is one of the most powerful ways to influence consumer perceptions of a wine. It is almost as if the beauty of the label, serving as the final finesse on any bottle, reflects the divinity of the wine inside the bottle. During a two-day forum held in Amsterdam, discussing so called “neuro marketing”, they further found that consumers of luxury goods, such as wine, are particularly influenced by pleasant colour combinations, thoughtful designs touches and a clear brand image recommending that producers and retailers, dealing with such goods, need to envelop the consumer in a complete sensory experience of the brand. An experience completely suited to the needs of a typical wine consumer, considering the importance aspects such as aroma, taste and ambience of a tasting room have on their decision to buy a wine, which experience can ultimately be summed up or revisited on the wine’s label.

The ban on alcohol advertising, proposed by the recently approved Control of Marketing of Alcoholic Beverages Bill, as well as the ominous threat of possible plain packaging regulations, similar to those contained in Australia’s Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 148 of 2011, from a wine label’s perspective, is clearly of great concern. Although very little is known about the details contained in the said Bill, it is foreseen that the culmination of the aforementioned will seriously restrict a wine consumers’ freedom of choice and also prohibit them from distinguishing wines from various demarcated regions, ultimately preventing consumers from choosing their wine of preference form a desired region. This will also leave wine producers in the dark, as wine consumers’ choices will no longer be able to guide them in consumers’ preferences and leave producers unable to profitably cater for consumers’ demands. Unable to choose a wine for its finely crafted content, consumers might fall into a habit of bargain driven buying which will have a tremendous negative financial effect on an industry already under severe economic pressure which might lead to even more exports, depriving locals of one of our country’s best home grown and produced products.

Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi, motivates the Control of Marketing of Alcoholic Beverages Bill by saying that alcohol has been found to be a major contributing factor in the majority of motor vehicle accidents and that it has also been linked to crime and violence in South Africa. Subsequently he feels himself obliged to protect the consumers of alcohol from their self inflicted bad habits by creating a “nanny state” in which the consumer’s freedom of choice is regulated to the point of extinction. Deputy Health Minister Gwen Ramokgopa wants to extend this protection by revising the regulations for labelling of alcoholic beverages to include health warnings. Considering the ministers’ stance against alcohol and tobacco products, and the parallels often drawn between these types of products, in view of the global developments in respect of plain packaging regulations for tobacco products, it might only be a question of time before similar regulations might be imposed on packaging of alcohol products, which includes wine labels. Having touched on the parallels between alcohol and tobacco, it must be stressed that the most effective anti-smoking initiatives have been multi faceted. Similarly, the problems with alcohol abuse are complex and often alcohol abuse is a mere symptom of a much larger socio-economic illness.

In a British study evaluating the impact of picture health warnings on cigarette packets the researchers concluded that:

“There were few changes post implementation of the picture health warnings in the number of health effects recalled or participant’s perception of risk…There were no differences post implementation of the picture health warnings in the number of smokers reporting forgoing a cigarette when about to smoke one or stubbing our a cigarette because they thought about the health risk of smoking…Among young people, the impact of picture health warnings was negligible.”

Considering the mentioned “neuro marketing” element in advertising of luxury goods, such as wine, it seems that the banning of any advertising in respect of these goods might only have an effect on the educated consumer who is looking for a specific product, while such banning might have no effect at all on the bargain driven consumer, who (it seems) is also the consumer most likely to overindulge.

In principle it is unfair to judge cigarettes and wine on the same basis. Cigarettes are the only products, if used as intended by the manufacturer, that are likely to kill you, whilst wine have a wide range of proven health benefits if used moderately.

It is absurd to think that people can be legislated into responsibly consuming alcoholic beverages. Notwithstanding the State’s good intentions, it can never replace a parent’s role in educating a person into responsibility. The negative impact such legislation will have on the liquor industry, its economy, sponsorships for sport events, intellectual property rights and employment far outweighs the remote possibility it might have in combating motor vehicle accidents, criminal activity and domestic violence on its own. A balance must be struck between state protection and a consumer’s right to sovereign choice.

In context of a wine label, the intended legislation put so much more at risk than the mere advertising of an alcoholic beverage. Blind legislation in this regard might also deprive us of the valuable trademarks, proud heritage, rich history, unique terroir, colourful stories and precious art depicted on and represented by wine labels.